A debate erupted on crypto Twitter recently over whether Layer 1 blockchains should be evaluated against Amazon or Microsoft using price to sales ratios. The conversation quickly became heated. Some argued that blockchains generate revenue just like companies do, making traditional valuation frameworks perfectly applicable. Others pushed back, insisting that comparing a decentralized protocol to a corporation fundamentally misunderstands what blockchains are. The argument spiraled into the usual online chaos, with both sides talking past each other.

Beneath the noise lies a more important question that neither side fully addressed. Price to sales ratios are more of a barometer than a valuation technique. Investors in a company or a Layer-1 blockchain token don’t actually receive sales. The former has a contractual right to the residual cash flows or profits, but the latter’s benefits of ownership are more obscure. More importantly, you cannot value what you cannot measure and right now, crypto lacks the foundational infrastructure needed to measure economic activity in a consistent, reliable, and comparable way.

Traditional valuation frameworks work because they rest on decades of standardized measurement. When an analyst decomposes the financial statements for a public company, they are not inventing a new methodology to draw out its value drivers. They are applying rigorous analysis on audited reports prepared according to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These accounting conventions create a common language. While the exercise often requires some level of art and science, revenue means the same thing for a retailer in New York as it does for a manufacturer in Frankfurt. Earnings are calculated using consistent rules. Assets and liabilities are classified according to agreed upon definitions. This standardization makes it possible to compare companies across industries, geographies, and time periods.

Valuation also depends on enforceable rights. When you buy a share of stock, you acquire a defined set of legal claims. You have voting rights. You may receive dividends. If the company is acquired, you participate in the proceeds. These rights are not ambiguous. They are documented in corporate charters, governed by securities law, and enforced by courts. An analyst valuing a stock knows exactly what economic interest the equity represents.

Crypto has none of this. Blockchains are not companies. Tokens are not shares. The economic models and data that underpin decentralized networks are not standardized, which makes traditional valuation frameworks impossible to apply in any rigorous way.

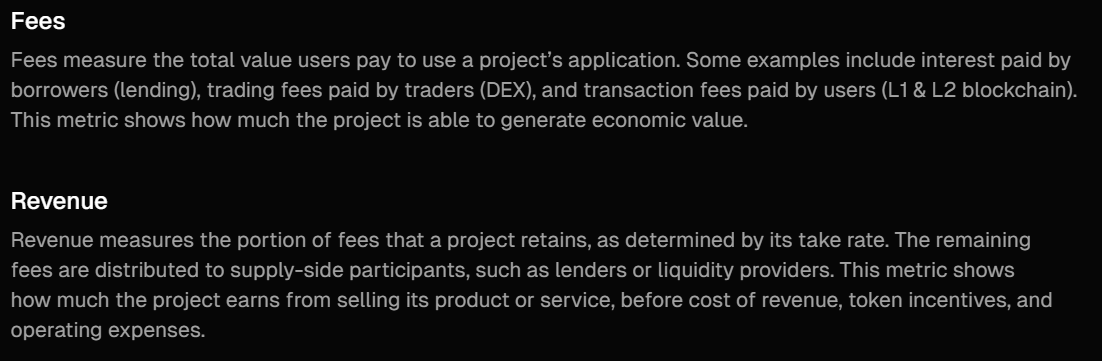

Start with the question of what revenue actually means in crypto. When someone says a blockchain generated ten million dollars in revenue last quarter, what are they measuring? In most cases, they are referring to fees paid by users to validators or stakers for processing transactions. But this is not revenue in the corporate sense. A company's revenue represents the inflow of economic benefits that the entity controls and can deploy toward operations, growth, or distribution to shareholders. Blockchain fees, by contrast, are payments made by users to compensate network participants for computational work. Whether those fees accrue to token holders depends entirely on the specific economic design of the protocol. Some blockchains burn fees, removing them from circulation. Others distribute fees to stakers. Some do both and some do neither, with fees going entirely to validators who may or may not hold the native token.

Source: Token Terminal

This variation isn’t necessarily a bug. It reflects the fact that blockchains are designed to serve different purposes and embody different governance philosophies. However, it does create a measurement problem. If two blockchains each generate ten million dollars in fees, but one burns those fees while the other distributes them to token holders, are they economically equivalent? Clearly not. Yet both might be described as having the same revenue, leading to misleading comparisons.

The rights conferred by tokens are equally inconsistent. Some tokens grant governance votes. Others provide fee sharing. Some offer both. Many offer neither, functioning primarily as a medium of exchange or a speculative asset. Unlike equity, where the bundle of rights is standardized and enforceable, token rights are defined by code, community consensus, and evolving governance structures. There is no uniform legal framework that guarantees token holders will receive anything, even if the protocol generates substantial economic activity. This means analysts cannot assume any economic linkage between network activity and tokenholder outcomes.

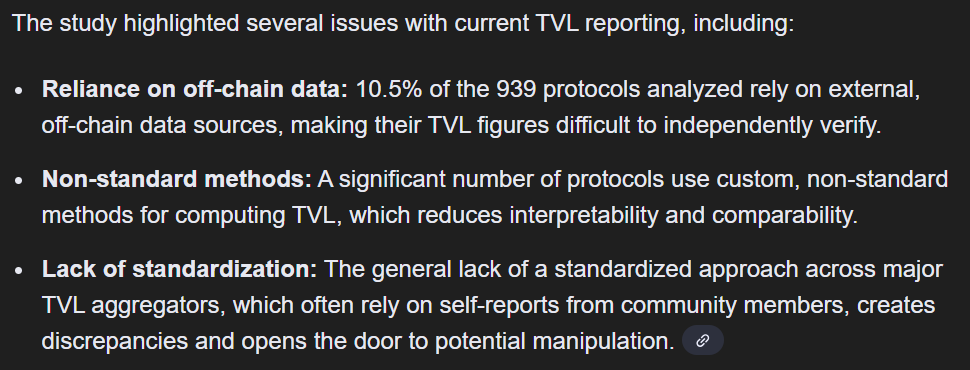

This lack of standardization extends to how data is collected and reported. Public companies issue quarterly financial statements that follow strict disclosure rules and are subject to independent audits. Blockchains do not issue financial statements. Instead, analysts try to discern on-chain data, which is transparent and verifiable but not organized according to any consistent reporting standard. Different data providers use different methodologies to calculate the same metrics. Total value locked, one of the most widely cited measures of protocol activity, can vary significantly depending on how the provider defines and aggregates the underlying data. A recent BIS study found that less than half of DeFi protocols had reported total value locked figures that matched independently verifiable on-chain calculations. Valuation models are only as good as the inputs that feed them, and crypto’s inputs are still inconsistent across protocols and data providers.

The crypto industry has recognized this problem and made meaningful progress toward solving it. Platforms like Token Terminal, DeFiLlama, Messari, and Dune Analytics have built infrastructure to surface structured data from blockchains and translate raw transaction information into metrics that investors can use. Token Terminal, for example, explicitly positions itself as establishing accounting and disclosure standards for the crypto market, providing real time financial statements for decentralized protocols in a format that resembles traditional corporate reporting. Messari produces standardized quarterly reports for major protocols, applying conventional accounting ratios and enabling cross protocol comparisons. DeFiLlama has become the industry standard for tracking total value locked, even as it grapples with methodological inconsistencies across the protocols it covers.

These efforts represent significant steps forward, but they also highlight how far the industry still has to go. Each platform uses its own definitions and methodologies, which means that the same protocol can show different revenue figures depending on which data provider you consult. There is no equivalent to GAAP or IFRS for blockchains. There is no standard chart of accounts, no agreed upon treatment of token emissions, no consistent way to classify transaction types. Analysts are left to cross validate metrics across multiple sources and make judgment calls about which methodology is most appropriate for the question they are trying to answer.

This data problem is not purely technical. It is also regulatory. The recent repeal of Staff Accounting Bulletin 121 is a useful example of how the data story is beginning to change. SAB 121 required banks and other financial institutions to recognize crypto assets held in custody as liabilities on their balance sheets, which created capital and accounting complications that discouraged institutional participation. The repeal removes that barrier, making it easier for traditional financial institutions to offer crypto custody services. But the significance goes beyond custody. When regulated institutions hold and report on crypto assets, they bring with them the disclosure standards, accounting conventions, and audit requirements that define traditional finance. This creates pressure for better data quality, more consistent reporting, and eventually more reliable metrics.

At the same time, the infrastructure for measuring on-chain activity is improving. Indexing protocols are becoming more sophisticated. Block explorers are offering richer analytics. Data providers are building unified schemas that make it easier to query and compare activity across different blockchains. The industry is moving toward standardized categorization of transaction types, which will make it possible to distinguish between genuine economic activity and wash trading or bot generated noise. These improvements will not happen overnight, but the trajectory is clear.

The implication is that valuation will become more defensible only once measurement becomes more standardized. Today we are in the early innings. Investors who try to apply traditional valuation frameworks to crypto are working with incomplete and inconsistent data. That does not mean valuation is impossible, but it does mean that any valuation exercise requires a much higher degree of judgment and a much deeper understanding of the specific protocol being analyzed. You cannot simply plug numbers into a workbook and expect a meaningful result. Frankly, this is the case in traditional equities too. Valuation remains both art and science.

Looking forward, the most important unlock for institutional capital over the next cycle may not be regulatory clarity or improved custody solutions, though both matter. Standardized data quality and project disclosures, while a burden on the teams will be a boon for investors. Institutions are accustomed to making investment decisions based on normalized financial information. They rely on audited statements, consistent metrics, and comparable disclosures. Crypto does not yet provide these things in a reliable way. Until it does, institutional adoption will remain constrained, not because institutions do not understand the technology, but because they cannot measure the economic activity it generates with the precision their investment processes require.

The debate over how to value cryptoassets will continue, and it will generate more heat than light. However, the real work is happening elsewhere. It is happening in the data platforms that are building the infrastructure to measure blockchain activity. It is happening in the regulatory conversations that are pushing for better disclosure and accounting treatment. It is happening in the on-chain analytics tools that are making it easier to track and categorize transactions. This work is less visible than the arguments on Twitter, but it is far more important. Crypto is still building the measurement tools needed for rigorous valuation. Once those tools exist, the valuation debate will finally be grounded in something real.

.png)